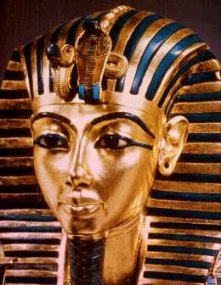

The Face of Moses

Is this the face of the young Moses?

The biblical story of Moses and

the Exodus is set around 3500 years ago. The precise date, however, was

until recently difficult to determine: the Old Testament does not provide

dates; neither does it name the reigning Egyptian pharaoh at the time.

Now, excavations of the ancient city of Jericho have made it possible to

place the Exodus story in an historical context. The Bible says that the

Exodus took place forty years before the Israelites conquered Jericho in

what is now the West Bank, and archaeologists have revealed that this city

was conquered by the Israelites in much the way the Bible relates. The

latest carbon dating places this event to around 1315 BC, with a decade

margin of error either way. This means, if the Bible is correct, that the

Exodus occurred sometime between 1365 and 1345 BC. So is there

historical evidence of Moses' existence during this time?

Moses and the Exodus

The middle coffin used for Tutankhamun's burial.

Prince Tutmoses

Some Egyptologists believe that

Prince Tutmoses returned to Egypt and was eventually buried there. If

this is true then he is unlikely to have been the historical Moses who,

according to the Old Testament, never returned to Egypt after the Exodus.

Tutmoses, though, was never buried in the tomb prepared for him in the

Valley of the Kings.

The assumption that he died in Egypt is based entirely on the discovery of a number of funerary items

bearing his name, which actually means nothing in itself. Funerary good

were prepared for the Egyptian royalty years before they died.

The Mysterious Coffin

Egyptian religion required

that a royal person’s burial should be extremely elaborate; if it was not

done properly then they would suffer in the afterlife. These burials

included a great many ritual items that were entombed with the deceased. This

all required years of preparation: tombs were dug, and burial

goods were made and ready, years before a pharaoh died. Sometimes,

however, these items were never used in the burial of the person for whom

they were intended: for instance, because an individual was disgraced,

overthrown or exiled. It is a little publicised fact, but many of the

burial goods in Tutankhamun’s tomb were originally made for others. The

reason being, that Tutankhamun died tragically young before all his own

funerary items were ready. One of these items was Tutankhamun’s coffin

- one that may originally have been made for Prince Tutmoses.

The death mask of Tutankhamun (left) and the face on the middle coffin exhibit very different features.

The Tutankhamun Enigma

When an ancient Egyptian

pharaoh was crowned he was given a throne name, in much the same was as

the Pope takes a new name when he becomes pontiff. Tutankhamun chose the

throne name Neb-kheperu-re – “Lord of [the god] Re’s Manifestations”.

This name was found inside the middle coffin, but closer examination

revealed that it had been inscribed over an earlier throne name that had

been sanded down and polished out. Microscopic analysis has now made it

possible for the original name to be discerned: Ankh-kheperu-re -

“Living Manifestation of Re”. This was, in fact, the throne name used by

Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessor, his older brother Smenkhkare. While

he was alive Smenkhkare had persecuted the Egyptian priesthood and, when

Tutankhamun died, these priests had no qualms about robbing his tomb to

furnish Tutankhamun’s. When Smenkhkare’s tomb was discovered in 1907 it

was found to have been robbed of all its burial goods. Only the mummy and

a single wooden coffin remained. This had not been the work of the usual

grave robbers, however, but had been officially sanctioned by

Tutankhamun’s priests who had resealed the tomb with their official seal.

When Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered fifteen years later, so also were

many of these missing burial goods. Dozens of Tutankhamun’s funerary

items were found to have been inscribed with Smenkhkare’s name. The

middle coffin, therefore, has been assumed to be one such item.

The Face of Moses

Egyptian princes often chose,

or were given throne names well before they became pharaoh, and the

various pieces of Prince Tutmoses’ funerary equipment that have been found

show that he also intended to reign with this throne name Ankh-kheperu-re. Tutmoses, of course, never became pharaoh and so

never used that name, which is why Smenkhkare later used it as his throne

name. The middle

coffin, therefore, could equally have been made for Prince Tutmoses, rather than

Smenkhkare. Certainly, a number of other items in Tutankhamun’s tomb had

originally been made for Tutmoses, such as the ivory whip.

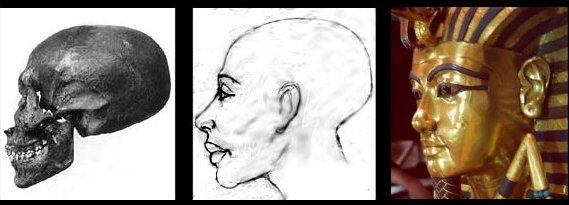

In the 1990s

scientific examination of Smenkhkare’s mummy made it possible to

reconstruct his face from the skull. The figure does bear a family

resemblance to Tutankhamun, as would be expected. It does not, however,

look anything like the figure depicted on the middle coffin. In

particular, the face has a much more extended profile to the flatter face

on the coffin. If the figure is not Smenkhkare, then it could well be the

only other person of the period for whom a coffin would have been

inscribed with the throne name Ankh-kheperu-re: Prince Tutmoses –

the man who may have been the historical Moses. If it is, then it is the

only lifelike representation of Moses ever found.

Reconstruction of Smenkhkare's face made in the 1990s shows a very different

profile to the figure on the middle coffin.

According to the Bible, for

many years the ancient Israelites endured slavery in Egypt. One

Israelite, Moses, was secretly adopted as a baby by an Egyptian princess,

and was raised as a prince at the Egyptian court. When he became a man,

Moses’ sympathy for the Israelite plight made him an enemy of the pharaoh,

the Egyptian king, who forced him into exile. Many years later, Moses

returned to Egypt and led the Israelites to freedom in the events referred

to as the Exodus.

In the Bible, Moses is raised

as the pharaoh’s own son, but after he is exiled and the pharaoh dies,

another son, Moses’ step-brother, becomes king. During most of the period

in question the ruler of Egypt was the pharaoh Akhenaten. Akhenaten did

indeed have an elder brother – Prince Tutmoses - who was heir to the

throne, but for some unrecorded reason, like Moses, he was exiled from

Egypt before he could become king. Could this Prince Tutmoses have been

the historical Moses?

Almost no records have survived

concerning Prince Tutmoses from which to say anything for certain. His

name is certainly interesting, though. The moses in his name is

Egyptian for “son”: his name means “Son of [the god] Tut”. (Tut is better

known by the Greek rendering of the name, Thoth.) If Prince Tutmoses

turned his back on the Egyptian gods as Moses did, then he might well have

dropped the Tut element from his name, shortening it simply to Moses.

Apart from

the moses element in his name, and the fact that he was exiled, there are

two other things Prince Tutmoses may have shared in common with Moses.

The Bible tells us nothing about Moses’ time as an Egyptian prince, but

the first-century Jewish historian Josephus records a number of traditions

associated with Moses that still survived during his time, 2000 years

ago. One was that Moses had at one time been a commander of the pharaoh’s

chariot forces. An ivory whip bearing Prince Tutmoses name was found in

Tutankhamun’s tomb; it is inscribed with hieroglyphics revealing that he

had at some point been the king’s chariot commander. Josephus also

suggests that while he still followed the Egyptian religion Moses had been

a priest in the temple in the city of Heliopolis in northern Egypt.

Inscriptions discovered in the ruins of the temple of the god Ra in

Heliopolis do indeed refer to Prince Tutmoses having spent time there as a

high priest.

Egyptian

mummies of the period were interred in a nest of three coffins, like a set

of Russian dolls, one inside the other. Two of the coffins made for

Tutankhamun bear his likeness depicted on his famous death mask. The middle coffin, however, bears the image

of someone with markedly different features. The lips of the coffin

figure are smaller; the face is broader and altogether flatter than the

figure depicted on Tutankhamun’s death mask and the other coffins; and the

image seems to represent someone in their early to mid twenties, whereas

Tutankhamun was only around seventeen when he died. So who was this

mysterious figure depicted on Tutankhamun’s coffin?

Strangely, although

Egyptologists have known for years that Tutankhamun was buried in someone

else’s coffin, it is virtually unknown outside academic circles that the

famous coffin does not bear Tutankhamun’s image. It is, in fact, one of

the images the world has come to recognise as Tutankhamun. It is found reproduced in photographs to promote all

manner of Egyptian-related material: posters to publicise books, brochures to advertise Egyptian holidays, and literature to support

Egyptian exhibitions. The fact remains, however, that it is not

Tutankhamun. But is it really Smenkhkare?