Page 4 of 11

The Chalice of Magdalene

The Shepherd’s Songs

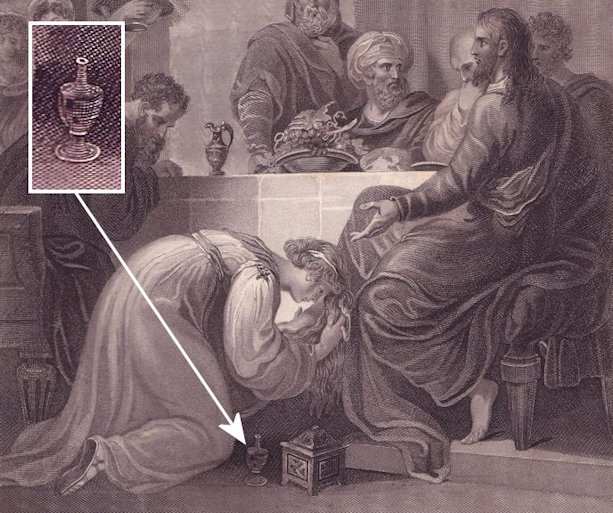

The only surviving picture of Wright's cup in an illustration by Victorian artist Arthur Mede.

The Whittington relic, said to be the Marian Chalice, disappeared until the mid-nineteenth century when one of Fulk’s descendents, a Shropshire writer named Thomas Wright, claimed that the cup had been handed down to him by his ancestors. It was described as a small stone cup made from green alabaster, also known as onyx. Only one depiction of it still survives, in an illustration made by Wright’s friend and contemporary artist Arthur Mede. In a biblical scene showing Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Jesus, beside her on the floor is the scent jar which she is said to have used to collect the blood of Christ. It seems to be about three inches tall, shaped like an eggcup with a lid. Rightly or wrongly, Thomas Wright was in no doubt that this cup was the original Holy Grail.

In 1855, with no children to hand it on to, Thomas Wright decided to hide the cup for posterity. Presumably seeing himself as some kind of latter-day Merlin, Wright claimed to have left an elaborate trail of clues that he said led to its hiding place. These were alluded to in a poem he published in 1855. Called Sir Gawain and the Red Knight, it tells the story of Arthur’s knight Gawain’s quest to discover the Holy Grail, which he identifies with the Marian Chalice. The story is set in Wright’s native Shropshire, beginning at the White Castle at Whittington and ending with Gawain finding the Grail at the Red Knight’s castle called the Red Castle. This was another historical medieval building, some ten miles east of Whittington in the grounds of the country estate of Hawkstone Park.

The remains of the Red Castle built into the cliffs of Hawkstone Park.

At the end of the poem, once he has drunk from the Grail, Gawain decides to hide it again in a new location. It is not revealed where he hides the cup, and the story ends cryptically with Gawain standing on the battlements of the Red Castle, looking out over the landscape and contemplating its hiding place.

The first page from Wright’s book.

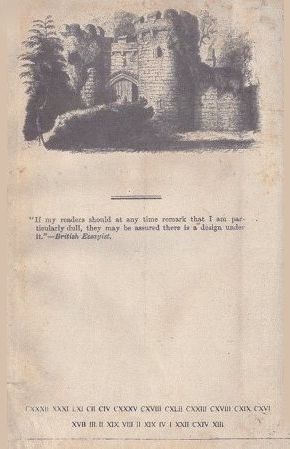

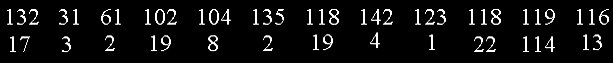

The final page from Wright’s book.

Was the Marian Chalice really hidden somewhere in the Shropshire countryside in 1855? Was it still there to be found? Did Thomas Wright’s poem really hold a secret message to reveal where it was? As no one seemed to have solved the riddle, in the 1990s - almost a century and a half after the poem was published - Graham Phillips decided to investigate.

On the opening page of the book in which the poem was originally published, there is an illustration showing the White Castle at Whittington and a cryptic quotation by an anonymous British essayist:

If my readers should at any time remark that I am particularly dull, they may be assured there is a design under it.

The design "under" the quotation was two lines of Roman numerals at the bottom of the page which in modern numbers were:

As they appeared to have no purpose or obvious relevance to the poem, Graham decided that these numbers may have formed some kind of code. But if it was a code, how could it be deciphered? After much research, Graham concluded that the final verse of the poem held the vital key to the code. On the last page of the book there was an illustration of the Red Castle, and under it the last enigmatic verse that read:

The Shepherd’s Songs to guide the way,

The horn was blown,

The treasure lay.

The horn was blown,

The treasure lay.

Could this mean that the "Shepherd’s Songs" would guide the way to the treasure – the Marian Chalice? If so, what were the mysterious Shepherd’s Songs?